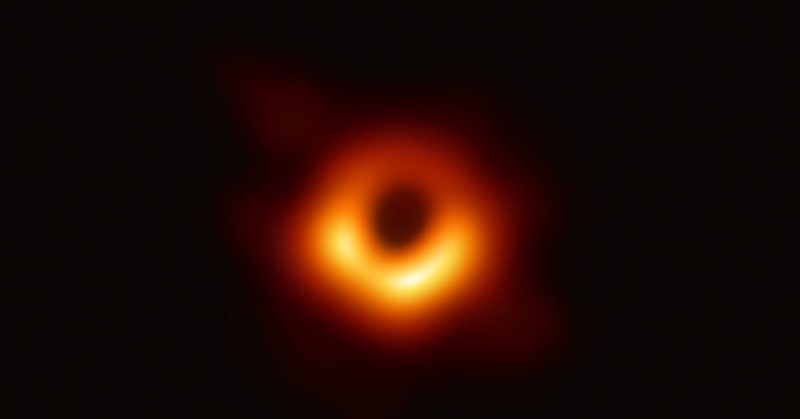

Scientists recently observed the formation of this mysterious Black Hole after two smaller ones merged together. The huge collision occurred 7 billion years ago but we were able to observe it now. The new event will give astronomers a deeper insight into these objects of nature.

Let’s put our scales in perspective first, we know that there were two black holes in this collision. One of which was about 66 times the mass of our Sun. The other was roughly 85 times the mass of our Sun. For those who don’t know the mass of our Sun is around 1.989 × 10^30 kilograms. So these were pretty huge objects.

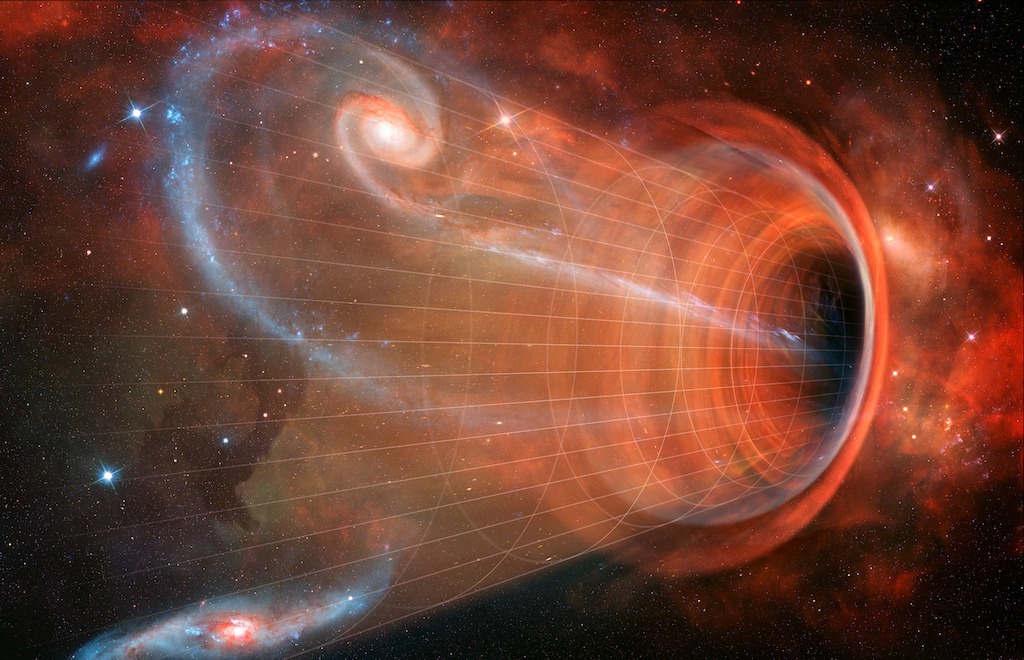

The two bodies spun around one another several times per second before eventually colliding together in a massive explosion that sent shockwaves throughout the universe. What became of them afterward is another black hole that is about 142 times the mass of Sun.

This new discovery would mean a ton of new knowledge for researchers. Up until now, scientists have detected various black holes through direct observations and indirect methods. In addition, they have also divided them into categories depending on their size.

The first ones are the smaller ones between five and 100 times the mass of our Sun. We also have supermassive black holes that occur at the centers of galaxies which are millions and billions of times our Sun’s mass.

Also read: NASA is now growing plants in space

While these two extremes exist with experimental observations. Scientists were pretty confident that a middle ground also existed in this size classification. The pursuit to find an intermediate-mass black hole has been going on for a long time now. Astronomers predicted that they will range from 100 to 1000 times the mass of our sun. Until now there was no hard evidence that these kinds of Black holes existed.

What We Discovered:

Salvatore Vitale, an assistant professor at the LIGO Lab of MIT talked about his study of gravitational waves with The Verge. He said that “They (Black Holes) are really the missing link between tens of solar masses and millions. It was always a bit baffling that people couldn’t find anything in between.”

This new discovery will help us understand our immense universe in more detail. Scientists think that since the smaller black holes are most abundant whereas the supermassive black holes occur only at the centers of galaxies.

The supermassive black holes get that massive with smaller black holes merging over and over. The process repeats until they form one enormous unit. If that were to be true, then there’d have to be intermediate black holes out there in the Universe somewhere. Consequently, it looks like this new discovery just proved this theory.

Scientists detect black hole collisions by measuring tiny shockwaves produced by them. When these massive objects like merge, they warp space and time, creating ripples known as gravitational waves. These waves are pretty small and get attenuated by many magnitudes before they reach Earth. Present-day scientists are pretty experienced at detecting these tiny gravitational waves thanks to observatories in the US and Italy.

These observatories are known as LIGO and Virgo and are specifically designed to detect these events. Since the debut of LIGO in 2015. The two observatories have detected roughly 67 mergers of black holes, neutron stars, and black holes merging with neutron stars.

Also Read: Scientists develop a device that can do photosynthesis artificially.

Because of very narrow and sensitive detection criteria, astronomers are considering the possibility that they may not have actually seen a massive black hole merger. Instead, they might have picked up waves from a collapsing star or some other unknown phenomenon. With that said, a black hole merger is the only explanation that makes sense right now from what they’ve observed.

Vitale is confident to observe mergers like this again. Currently, LIGO and Virgo are online and not making observations. The two facilities will be back online by the end of next year. After some upgrades making their instruments even more sensitive than before.